I’ve been getting more and more emails lately from people asking, “What is an epic, a feature and a user story in agile?” “Can you give me some epic, feature, and user story examples?” “Can you tell me how to write epics, features and user stories?”. "Epics? User Stories? What's the Difference?"

So in this article, let’s cover some basic—but very helpful—territory by explaining some user story–related language.

Stories, themes, epics, and features are merely terms agile teams use to help simplify some discussions. Some of these terms date back to the days of Extreme Programming (XP) teams, but the terms are used in newer ways now. I’ll start with industry-standard definitions, and I’ll comment on the changes as well.

Epic vs. User Story

When it comes to understanding the difference between epics and user stories it helps to understand what each is.

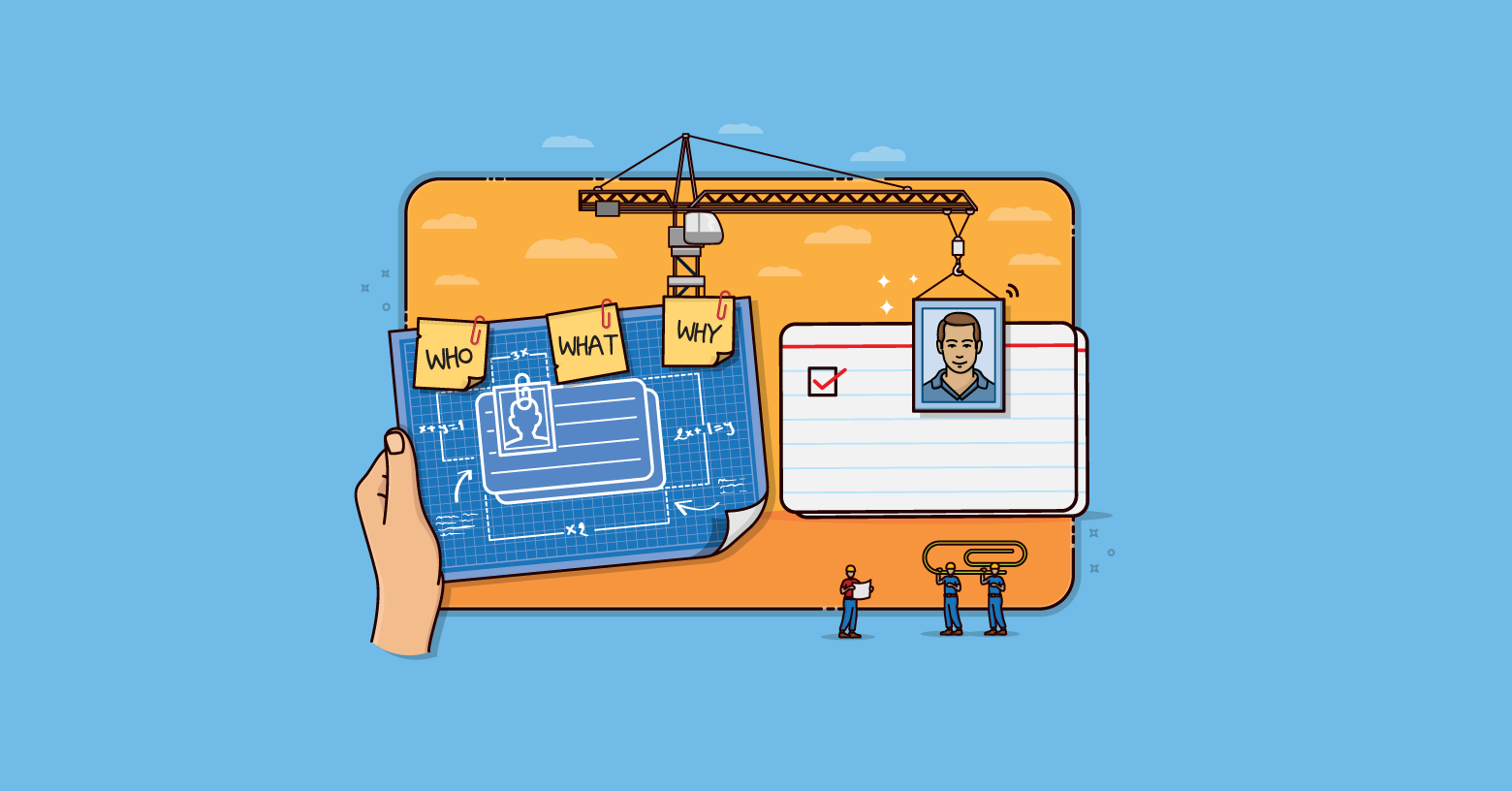

A user story is simply something a user wants. For our purposes here, we can think of a user story as a bit of text saying something like, “Paginate the monthly sales report” or, “Change tax calculations on invoices.” There is more to user stories than just text written on an index card or typed into a tool, but let’s keep it simple here.

User stories are the most common form of product backlog item for agile teams. During sprint or iteration planning, user stories are moved from the product backlog to the sprint backlog.

Many teams have learned the benefits of writing user stories in the form of: “As a [type of user] I [want this thing] so that [I can accomplish this goal].” Check out the advantages of that user story format. Even within the format, though, we’re free to customize user stories.

As defined by the XP teams that invented user stories, an epic is a large user story. There’s no magic threshold at which we call a particular story an epic. For our purposes in agile and Scrum, epic just means big user story.

I like to think of this in relation to movies. If I tell you a particular movie was an “action-adventure movie” that tells you something about the movie. There’s probably some car chases, probably some shooting, and so on. The term I used tells you this even though there is no universal definition that we’ve agreed to follow; no one claims an action-adventure movie must contain at least three car chases, at least 45 bullets must be shot, and so on.

While epic is just a label we apply to a large story, calling a story an epic can sometimes tell us how refined they are in the backlog.

Suppose you ask me if I had time yesterday to create user stories about the monthly reporting part of the system. “Yes,” I reply, “but they are mostly epics.” That tells you that while I did write them, most are still pretty big chunks of work, too big in fact to be brought directly into a sprint or iteration. Remember that the Scrum framework doesn't say anything about epics, stories, and themes. These terms come from XP.

Theme vs. User Story

The team that invented user stories used the word theme to mean a collection of user stories. We could put a rubber band around that group of stories about monthly reporting and we’d call that a theme.

Sometimes it’s helpful to think about a group of stories, so we have a term for that. Sticking with the movie analogy above, in my DVD rack I have filed the James Bond movies together. They are a theme or grouping.

Feature vs. User Story

One more term worth defining is feature. This term was not used by the original user stories team, which has led to feature being applied to different things in different organizations and teams.

Most common is that a feature is a user story that is big enough to be released or perhaps big enough that users will notice and be happier. Many teams work with user stories that are very small. Some of those teams find it useful to have a term they can apply to stories that are big enough to release on their own.

I’m not a big fan of the extra complexity one more term brings, and I find it a demotivating waste of time when teams get caught up in arguing whether a certain story is a feature or just a story, for example.

If you want to use feature, I recommend using it as a tag that can be applied to any item in your product backlog. A friend posts photos on Instagram of amazing meals he makes. He tags them with #yum. Do the same with #feature if you find it helps people work with your product backlog.

Confused? Your Software May Use These Terms Differently

If at this point you want to tell me I’m wrong, remember that I am describing these terms as defined by the team that invented user stories.

Some of the product backlog tool vendors use the terms differently. Jira, for example, uses epic to mean a group of user stories rather than a single, big user story. I do not know if this was a mistake on their part or not. But, a well-known vendor lock-in strategy is to manipulate the vocabulary so users think all other tools use the words incorrectly.

Here's the good news: While the ideas behind the terms can be useful, the terms themselves are not very important. Theme, epic, feature, and user story are not terms with important specific meanings like pointer to a programmer or collateralized debt obligation to whomever deals with that.

Don’t fight your tool—whatever term your software uses to mean small story (user story) group of stories (theme) or big story (epic)e is the term you should use.

Visualizing the Differences

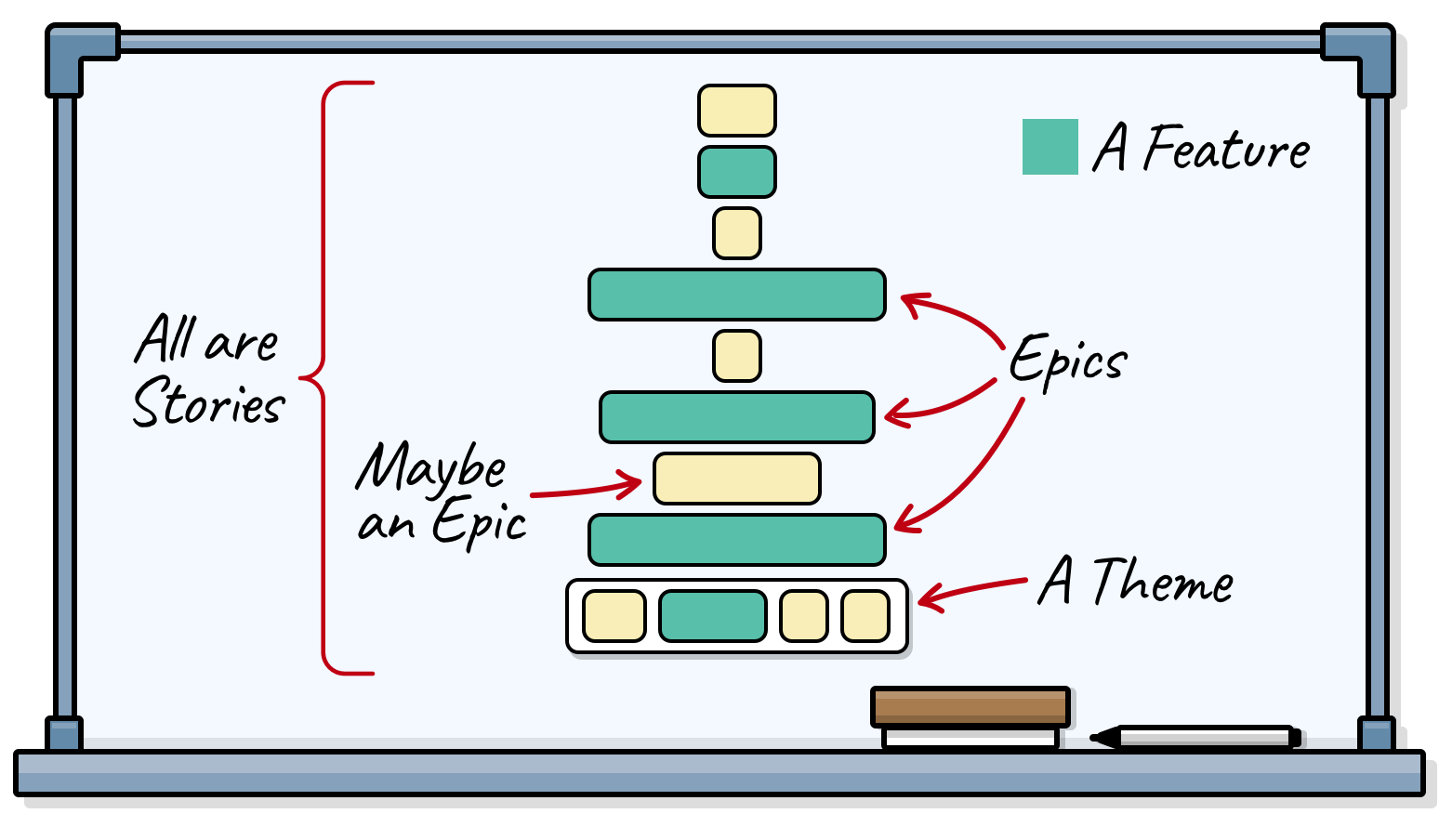

The following illustration of a product backlog makes clear the difference between story, epic, and theme. Each box represents a product backlog item with the boxes drawn to show the size of the different items. Some items are small and thus quick to develop. Other items will take longer and are shown as bigger boxes.

The big items are epics. One item is maybe big enough that some on the team would call it epic, but not so big that everyone agrees. This reflects the fact that there is no precise threshold at which an item becomes an epic.

The illustration also shows a theme, which is depicted as a box grouping a set of stories together. Themes are not necessarily larger than epics. A theme can be larger than an epic if, perhaps, you have a theme comprising eight medium-sized stories. But a theme can be smaller than an epic, as would be the case if you have a theme of a dozen simple spelling errors to correct.

And since feature usually means an item that can be released on its own, those are shown in green.

An Example of How these Words Are Useful

Let’s suppose we’re building some sort of financial system that will include a set of reports. Since we’re just starting development, we’re not too concerned yet with exactly which reports those will be. But we don’t want to risk forgetting we need to develop the reports, so we write a product backlog item as the user story:

As an authorized user, I can run reports so that I can see the financial state of the organization.

Not only is this a user story, it’s an epic because it’s too big to fit in one sprint or iteration. There are almost certainly going to be more reports needed than can be done in a single sprint or iteration. So we call this an epic.

Our reporting story/epic just stays as it is on the product backlog for awhile, perhaps a few months. One day the product owner decides that the team will work on these reports in the next iteration. That means the epic is split into a set of smaller stories, perhaps something like:

- As an authorized user, I can run a profit and loss report…

- As an authorized user, I can run a cash flow report…

- As an authorized user, I can run a transaction detail report…

and more. Let’s say we identify ten reports. A few days after splitting out these ten stories from their parent epic, the product owner announces a shift in priorities. Instead of working on reports, the team will be working on something completely different.

The product backlog could now look cluttered because there are ten small reporting stories where there used to be a single epic. To reduce this clutter, consider grouping the ten reporting stories into a single theme labeled “Reporting.” If your software tool supports this, it can make it easier to look through a backlog because you’d see one Reporting theme rather than ten distinct reporting stories.

Last update: June 24th, 2024